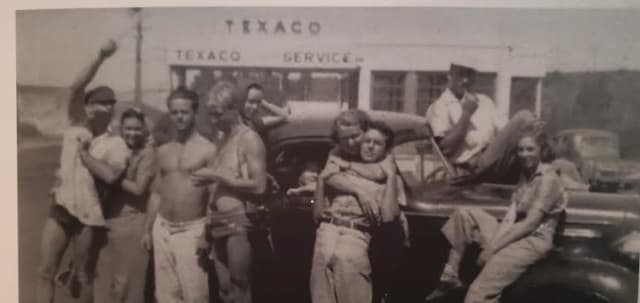

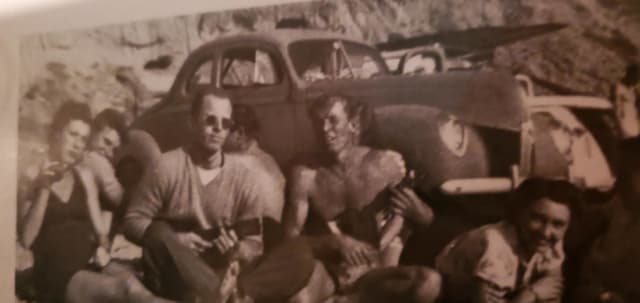

The serene morning of December 7, 1941, at San Onofre started like any other—a clear sky, hot sun, thin clouds, and surf around five feet. Bud “Augie” Anderson and his surfing buddies, just back from a movie night at the Miramar Theater in sleepy San Clemente, were gearing up for a mid-morning surf session.

“Bill Roth came paddling out,” Augie recalled, “and shouted, ‘Hey, the Japanese just bombed Pearl Harbor!’ We didn’t believe him at first, so we went in and turned on our car radios. That’s when we heard President Roosevelt declare war against Japan.”

Doug Craig, who would later become the President of the San Onofre Surf Club, was also surfing that morning. His bride-to-be, Bobbie, ran down to the water’s edge to flag him in and deliver the news.

“Another San Onofre regular, Stanford Kin, and I were stationed at Los Alamitos Naval Air Station,” Anderson, who joined the Navy in June 1942, recalled. “I surfed the whole summer of ’42 with my buddies at San Onofre.”

But that winter, Anderson shipped out. “I stayed in the Navy through World War II and the Korean Conflict. I didn’t surf much during those years.”

The same winter, the Santa Margarita Ranch property was taken by Eminent Domain by the U.S. Department of the Interior and leased to the Marine Corps, becoming Camp Pendleton’s training base. The quaint fish camp on the beach lost its lease, and its owner barely managed to hold onto his petrol station and café across Pacific Coast Highway.

The Marine Corps quickly clamped down on San Onofre surfing for security reasons, shutting down all public access to the beach. The once-busy surf spot was empty during the war years as surfers, like everyone else, were called into military service in the far corners of the Pacific and European theaters of the war. The great surfing legend Pete Peterson and many other top watermen were prized personnel for the Navy’s underwater demolition team, a precursor to the Navy SEAL units. Many, Anderson remembered, did not return.

“The war took the best,” he would often say.

With gas rationing and surfboard materials in short supply, even those not sent overseas had little appetite for leisure activities like wave-riding. For a few dreadful years of global conflict, the sweet life of San Onofre surfing almost ceased to be.